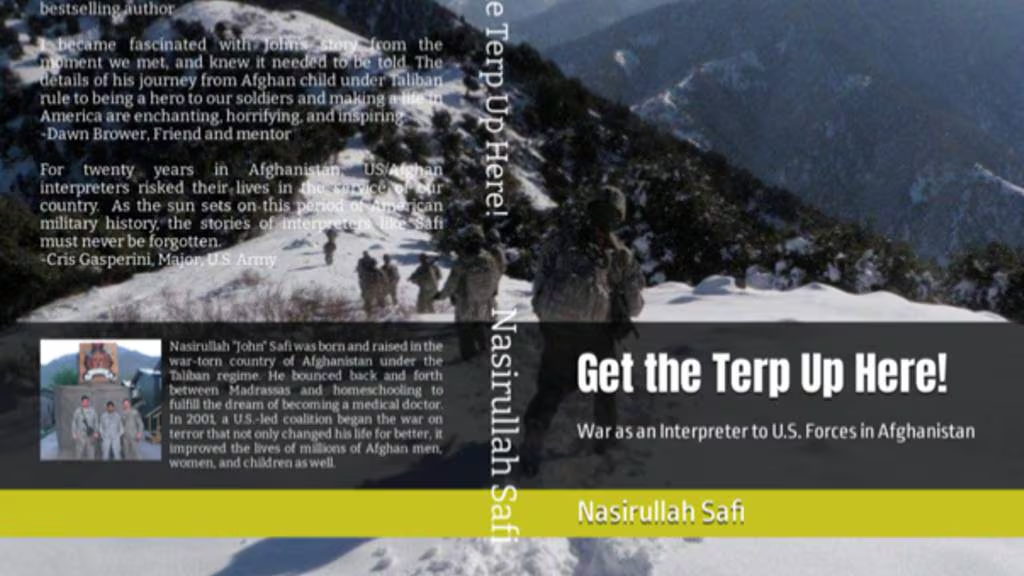

Get the Terp Up Here’ is Nasirullah “John” Safi’s eyewitness account of his time assisting U.S. forces as an interpreter in Afghanistan. (Courtesy: Nasirullah “John” Safi)

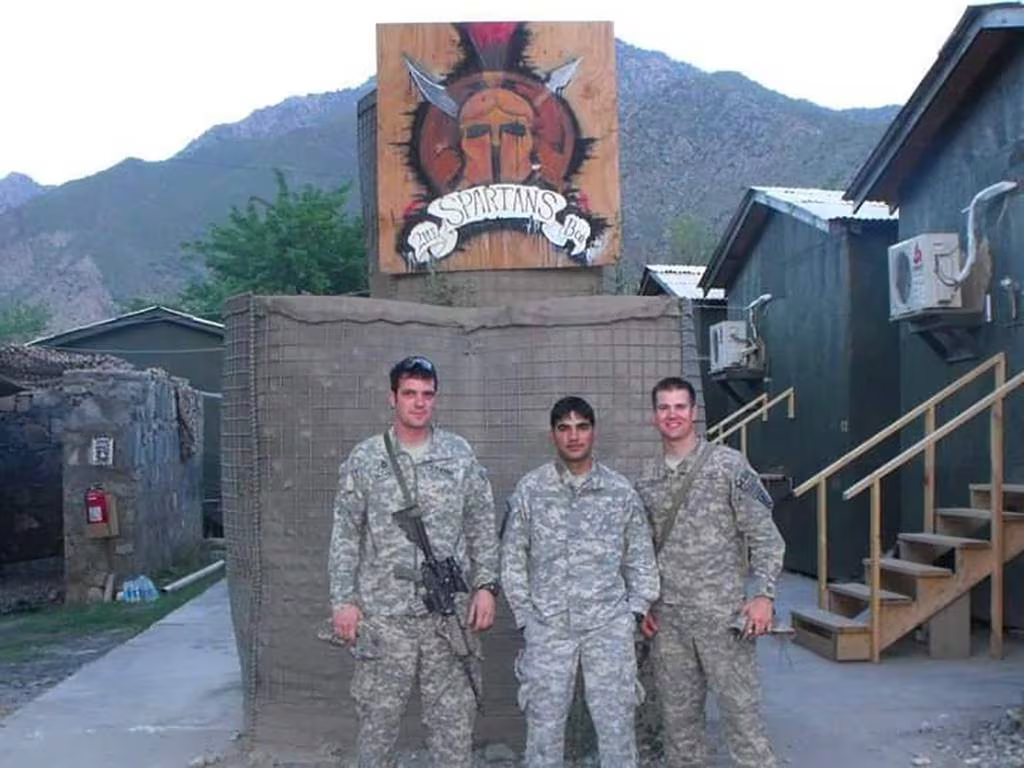

America’s partners in Afghanistan face difficult dangers. Nasirullah “John” Safi was born under Taliban regime. Later, he risked his life as a combat interpreter and cultural advisor for U.S. military and civilians.

John’s desire to learn started at a young age, but many schools were closed because of radicalism and extremism. He bounced between Madrassas and homeschooling with the hopes of becoming a medical doctor. John says his life, and the lives of millions of Afghan men, women, and children were changed for the better when the War on Terror started in 2001. John became an interpreter for the U.S. military in 2008. He was 15 years old.

October 2009

“Johnny boy, we are gonna need you!” SFC Devine called.

“I am about to go home on leave.” “I know, but I’m sorry we need you.” “No worries, I will see you in a little bit.” I had no clue what was going on when I headed over to his barracks still in my Afghan clothes. “John, we’re probably need you, we asked Hemat to work, but he is fucking very sick, otherwise I would take him,” Lt Kerr explained.

“What about the rest of the other interpreters?” SGT Hall asked. “We can take one of them if John wants to go home.”

“They are pussies. I already talked to LT Forcy, and none of them wants to go,” SFC Devine told us. “John, I will get in touch with you when we know more, but what the heck you have it on right now?”

“It’s Afghan traditional clothes.” “He looks like the Taliban,” SSG Benson chimed in. “John, the Taliban,” SGT Anderson joked. “I’m supposed to go home today. I wish I could travel with UCP uniform.” “Well, you can wear your uniform to Kamdesh,” SSG Anderson shrugged.

Kamdesh literally means “Place of the Kom.” It was an unofficial capital for the Kom tribe, but now it’s a small town and a district in the middle of the Hindu Kush mountains in Nuristan Province. It’s comprised of other small villages, which have their own language, culture, and traditions. It’s a beautiful, remote mountainous region in eastern Nuristan Province that’s approximately 350 kilometers from the capital city Kabul. People who live there are called “Nuristani”, which means “beauty” or “light” because its people are beautiful. Kamdesh and Nuristan are popular for their natural beauty and are the consolidation point for two rivers flowing from Barge-Matal and the Nechangal mountains.

I had never been to Kamdesh before, but I heard my second oldest brother, Ajmal, talk about it while he was driving supply trucks. It had never been a safe place, and my brother had lost many fellow drivers to the Taliban insurgents. The image of tough terrain and a district center without buildings was something that I still remembered about Kamdesh from my brother’s stories.

In addition, the local government was run by a local shura of 50 local elders who had long-held hostility with the Taliban insurgents as a result of decades-long conflicts over private property, water channels, and forest. These fights had killed many men from each side.

In 2009, this beautiful land experienced one of the bloodiest and most despicable battles of the war. COP Keating was a joint base for both Afghan and American soldiers from the 3rd Squadron, 61st Cavalry unit and was located deep in the valley, surrounded by high Hindu Kush mountains. The main goal of building COP Keating was to intercept and prevent the Taliban and other insurgent groups from transporting supplies to Kunar and eastern Nuristan Province and to be a base for counterinsurgency missions. The Afghan and American soldiers who watched over the valley from COP Keating and its observation post (OP), Fritsche, were under frequent and often simultaneous attacks from the Taliban insurgents, who attacked daily with snipers and mortars.

In October 2009, a daily attack turned into a large battle as hundreds of insurgents and foreign fighters tried to seize Keating.

More than 300 insurgents attacked the COP and OP from all sides with RPGs, mortars, snipers, grenades and machine-gun rifles. Meanwhile, in the Dangam Valley, 1st platoon [1-32] was busy as usual, conducting its daily patrols and missions, however, soon we were told to standby to possibly head to COP Keating to provide assistance. This would be another dangerous mission after the battle of OP Bari-Alai. It wasn’t clear whether the mission would take place or get canceled, but we had to be ready.

“Make sure you get everything this time, Johnny,” SFC Devine joked.

“I did, but I hope it never rains there,” I told him, this timing packing the rain gear that I had forgotten at Bari-Alai.

SFC Devine laughed and added, “You never know buddy.”

“Got enough batteries for the radio?” LT Kerr added. “I got enough.” The whole time I packed, I hoped for word that the mission was canceled so I could go home. I had not seen my family in months. I missed my mom badly, and I had told her that I was going to see her soon before we were assigned to the mission.

At the end of the day, it turned out that we were going into the Battle of Kamdesh. I met up with everybody at the helicopter landing Zone (HLZ) where we got airlifted to COP Keating. When we touched down, it was a complete disaster zone — dead Taliban and Afghan security force and local police force bodies were everywhere. We believed that some of the police were insiders who supported the Taliban during the attack and had turned their weapons against the American troops.

The fight wasn’t over yet. LT Kerr’s platoon [1-32] was among the first support to arrive. We ended up landing at the nearest observation post (OP) in order to secure it from possible attacks and conduct search-and-clear operations before we descended to COP Keating. We had to walk through rocky terrain in the forest get to the COP. Even though the militants were on the run, Taliban remained in the area to evacuate their dead and wounded. We planned for an enemy ambush on the backside of the mountain. When we did engage, we didn’t receive any casualties, but three Taliban insurgents were confirmed killed.

“Anything on the radio?” LT Kerr asked me.

“The Taliban speak more than one language here,” I replied.

“I heard them speak Nuristani, Urdu, Arabic, Pashtu and one more language that I couldn’t tell.”

“Are they talking about us?” SFC Devine asked.

“I think so because I heard them talk about our helicopters landing.”

We kept pushing and finally made it to the COP by 6 P.M. without more firefights. There was nothing left at Keating. Everything had been set on fire; while some of the barracks were still burning, the defensive barriers (HESCOs) and restrooms were already burnt to the ground. First platoon [1- 32] conducted its search-and-clear operations in the remaining areas of the COP, but we didn’t find anything other than the enemy’s dead bodies and blood everywhere. I had not seen or experienced anything like the nightmare that took place in the Kamdesh District that day. More than a hundred Taliban insurgents and foreign fighters got killed during the attack. Our radio scanner intercepted people speaking Urdu, Arabic and local languages while they searched for missing fighters–

“Mobariz, Mobariz, can you hear me?!” Ezam called. “Ezam, I can hear you,” Mobariz responded. “Mullah Saab says to let all friends know to take a great care with the aircraft.”

“The Americans just dropped bombs closer to Bar Kaley [upper village].” “Did you check on friends if they are okay?” Ezam asked “I tried, but their radios not working,” Mobariz said.

“Okay, may Allah keep you safe,” Ezam spoke and right after that, there was a big boom in the background sounded like another bomb dropped.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Kamdesh, eight American soldiers were dead and twenty-seven wounded. The survivors of the Battle of Kamdesh and COP Keating were awarded high military prizes including SSG Clinton, who received the Medal of Honor by President Obama in 2013.

Some ANA soldiers and Afghan private security guards were killed and wounded during the attack. A local police chief who was taken hostage by the Taliban insurgents was brutally killed because he refused to help them against American and Afghan troops. There were other policemen who ran off the base and joined the Taliban against American and Afghan forces. Many of them were killed during the attack. The massive attack had been well-planned, and Taliban insurgents managed to attack the COP and OP from all sides. Many ANA soldiers fled their locations on the eastern side of the COP, despite the efforts and hard work of two Latvian advisors who tried to protect those firing positions. There were rumors that the Afghan forces couldn’t keep their position due to shortages of ammo and close combat with the Taliban insurgents.

Shortly after the battle, we all evacuated the COP, and Keating was bombarded to make sure that it was completely destroyed so that Taliban or other terrorist groups couldn’t use it. In retaliation, the Taliban insurgents began targeting locals, who had supported Afghan and American soldiers while they were at COP Keating. The Taliban brutally killed many local residents and their houses were set on fire. Those suspected of supporting Americans were isolated and unable to travel to any nearby towns for shopping because the Taliban believed that they would tell the Afghan and Americans about the insurgent positions.

This hard punishment lasted until the Taliban commander, Mulawi Sadiq, joined the Afghan government. He was popular for his extremism and major involvement in the attack against the Afghan and American soldiers at COP Keating. However, after the diabolic and outrageous activities by the Taliban against innocent residents in Kamdesh District after the troop’s complete withdrawal on 6 October 2009, Sadiq turned against the Taliban. Once, he came under attack by the Taliban and his son attempted to carry out a suicide bombing to kill his father, but he did not succeed. Later, Sadiq would survive three other suicide bombing attempts, but nine innocent women who were farming got killed.

The former commander began to bring local tribal elders together to fight against the Taliban insurgents. Sadiq was able to establish a local shura comprised of almost a hundred tribal elders and residents from all villages of the Kamdesh District to ensure that the district was run in support of the Afghan government. Men, women and even kids who could find firearms were recruited to secure their own villages against the Taliban. Throughout the district, the main focus became survival. Parents began teaching their kids the basic skills for being a great fighter rather than have them going to school so that they could defend their families, farms, villages and houses from the Taliban and other terrorist groups.

This portion of “Get the Terp Up Here! War as an Interpreter to U.S. Forces in Afghanistan” is Nasirullah “John” Safi’s eyewitness account of the Battle of Kamdesh, depicted in the movie The Outpost. ©2021 Nasirullah “John” Safi.

Nasirullah “John” Safi left Afghanistan in 2016. He is a speaker at Duke University. Many of his family members are still in the country, and he is trying to help them to safety.

Editor’s note: This is a book excerpt and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an excerpt of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.